Andrew Nurse is Associate Professor of Canadian Studies at Mount Allison University where he teaches courses on public history, landscape, and alternative politics. You can read his article in the Journal of the Canadian Historical Association / Revue de la Société historique du Canada, vol. 34, no. 2 (2024) by clicking here.

Can you tell us about the changing relationship surrounding statues and public memory/public history in connection to US historical figures?

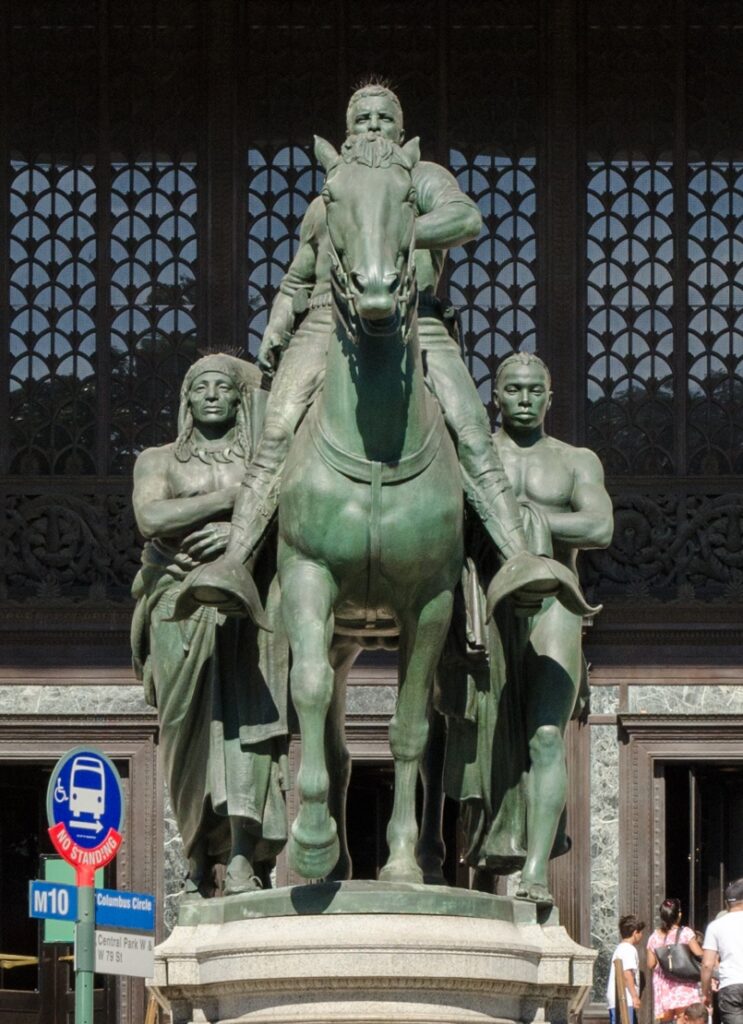

This is a difficult question to address a succinct way. Statues of key historical figures have clearly become part of the contested terrain of modern American memory. The different views, however, don’t always break down in a simplistic one side verse another way. That happens. But the statue I wanted to address – the Theodore Roosevelt Equestrian Statue – illustrates a concerted effort to find a different approach to the problem of rightly controversial statues. The relationship is changing because of the ways in which public memory is more overtly contested, and this relates to changes in the character of American public life. Public memory in the United States has always been contested and we should not forget that. If we do, we neglect the important work done by historians, museum workers, educators, and activists in the past. This included the difficult work of establishing accurate representations in the public sphere around Black American history, gendered and labour history, among others. I don’t want our situation amidst a set of current debates to lose sight of work that has often been very difficult and controversial.

I also want to say that this situation is not simply something that is going on only in the United States. That might be self-evident, but I think it is worth reminding ourselves. We are in the midst of a period of particularly vibrant debate about the scope, character, and meaning of public history and commemoration in Canada. The debate has not always been a debate. To be sure it has involved some nasty invective and, frankly, some outright misuse of history and a misapplication of historical methods. With all that in mind, I’d like to believe that we are at a point where we can have different and more informative discussions both about statues and what they tell us about history. I recognize that that might seem overly optimistic. The beginning of a discussion is a beginning. It is not a broad shift in views. If we bear that in mind, we might look at current debates from a perspective that encourages engagement and provides some space for guarded optimism.

To what extent has complexity hindered the interpretations surrounding the statue of Roosevelt and the Addressing the Statue exhibition?

History is about complexity but, in my view, the word is often used in a remarkably ahistorical way. In the case of the Equestrian Statue, or other controversial statues (including those of John A. Macdonald, among others, in Canada), the word complexity is used to explain away deeply disconcerting elements of the past. The argument usually runs something like this: all people are complex, no one is good or bad but some combination, we all did things we might regret or with mixed motives or, in hindsight, we might have done differently. Why should we fault Roosevelt, say, for being just like us? This use of the word complexity becomes a way of exempting a person from critical assessments of the role they played in history. This might seem like a good argument because historians talk about complexity all the time. It seems to fit with what historians are saying.

The problem is that this is not what historians mean when they use the word complexity. They don’t use it to explain away, or excuse, disturbing behaviour. They use it to explain the diverse factors that affect historical events and processes. I’ll give you an example. We might argue that the causes of the American Civil War were complex. By that historians mean that there were a range of factors that led to secession and war. They don’t mean that it was OK to hold slaves. In fact, rather than excusing slavery, they would ask a very different question: what circumstances led one group of people to believe that it was OK to hold another group of people in bondage?

This idea of complexity is, in my view, far more valuable than some sort of exculpatory approach to the term which, by the way, we all reject. No one, for example, would argue that the complexity of the World War II excused the Holocaust or the complexity of establishing the Soviet state somehow excused Stalin’s purges, gulags, and starvation programs. Said differently, I think the complexity of the past is incredibly important for us – those who study it, teach it, learn it, display it, etc. – to our work. But we need to use the term as an analytic concept in the right way. If we don’t, we end up producing history that is remarkably ahistorical.

Theodore Roosevelt Memorial Hall Entrance, American Museum of Natural History, New York.

Image by: edwardhblake under Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic

You wrote that “…if [the statue’s] intention was to honour Roosevelt as a conservatist then a different kind of imagery was needed.” Could you imagine how a statue that commemorates Roosevelt’s conservation efforts would look like?

Conservation is an important subject in both the United States and Canada. It should be. The problem with the Roosevelt statue is a problem that haunts other statues that supposedly mark other historical processes: they don’t do it. Instead, the Roosevelt statue – whatever its potential implications – was about venerating Roosevelt. It gained credence as some sort of marker of conservation only to the extent that one was willing to accept the idea that Roosevelt’s conception of conservation was, in fact, correct. Current historical research sees conservation in a different light because we are asking different questions about the past that is allow us to produce a different – and, in my view, more accurate – conception of the history of conservation; that is: conservation took place within a framework determined by colonialism.

What do I mean by this? As historians we necessarily see context as an important factor in history. In this case, the context of conservation was the dispossession of Indigenous Peoples. Whose land, after all, was being conserved? For whom? What happened to the people who lived on it? How did the state view them and their potential as guardians of nature? In Roosevelt’s case, of course, the Equestrian Statue makes absolutely no reference whatsoever to conservation. Its imagery – I’ve tried to argue – is better seen as an imperialist fantasy. Exactly how imperialism becomes a stand in for conservation is not something that is, to me at least, self-evident. It is something that we need to investigate; not something we should assume before we have actually done any research into the subject. Historians of Roosevelt have done this. I’ve cited some of them in the piece I wrote on this subject. They ask important questions about what conservation meant at given points in history? How did it reinforce specific and particular conceptions of nation and, in the case of Roosevelt, masculinity?

In the case of Roosevelt, in my view, it would be very difficult to create a singular kind of monument that commemorated his conception of “conservation” if we want to be true to historical methods and the research that has been done. Creating an iconography of Roosevelt that marks him simply as a conservationist rips him from his context (something historians should be loath to do) and celebrates what is at best an incomplete story (something else historians should be loath to do).

I don’t want to avoid your question: what would that statue look like? It might not be of Roosevelt. He is part of the story – as I’ve indicated above – but in restoring accuracy and context to that story, it would necessarily need to be presented in different ways. Instead, if we were looking to create historical markers of conservation, we might tell look to studies in environmental history that explore the changing ways in which nature has been represented and the changes in nature itself. I live close to an Indigenous community that has a publicly accessible medicine walk. If one were interested in nature, I can think of no better place to begin.

In addition to the Roosevelt equestrian statue, the commission noted three other statues that needed immediate action. Do you know what happened to them?

I’ll confess I have not really been following those. There has been a great deal of controversy and a legal decision regarding the Columbus Statue in Syracuse and that might be a good case study to engage in because it looks at how public memory has been legalized. That is one of the projects I am thinking about working on in the near future.

Have you read anything good recently?

That would be a great title for a historical blog. My answer is yes but that is not surprising for historians, is it? Non-fiction: I recently finished William Gibson’s The Peripheral. Fascinating story. I think cyberpunk has its own interesting historical consciousness. The most interesting non-fiction work I’ve read recently is John Leroux and Emma Hassencahl-Perley’s Wabanaki Modern. I’ll also put a plug in for katherena vermette’s graphic novel A Girl Called Echo (with Scott Henderson, illustrator, and Donovan Yaciuk, colourist). It is a captivating story about a time-traveling Métis teenager. We used this book in our intro this past year and it was great.