Leila Inksetter is a professor in the Department of History at the Université du Québec à Montréal. Jérôme Morneau holds an MA in history and is a historian working for the Ministère des Ressources naturelles et des Forêts of Quebec. Louis-Pascal Rousseau holds a PhD history and is a researcher who has worked in various academic institutions (Université Laval, Université du Québec, University of Pennsylvania and École des hautes études en sciences sociales). He is also a consulting historian on Indigenous issues for the Canadian federal government, as well as for provincial governments and First Nations organizations. You can read their article in the Journal of the Canadian Historical Association / Revue de la Société historique du Canada, vol. 35, no. 1 (2025) by clicking here.

In what ways did the presence or absence of paternal involvement shape the social identity and cultural affiliation of mixed-ancestry individuals?

Until the 1830s, the Euro-descendant men involved year-long in the fur trade along the Upper Ottawa River were vastly outnumbered by Anishinaabe people, and they did not stay for prolonged periods at any given post. Some of those men engaged in marital relationships with local Anishinaabe women, but these unions rarely lasted for more than a few years. When the men’s contract ended, the couples split apart, and the men departed, leaving their country wives and country-born children behind. In that context of limited paternal involvement, the children born from these unions were socially integrated into Anishinaabe society.

Starting in the 1830s, settler society progressed northward along the Ottawa River Valley. The colonial frontier provided economic alternatives for the men who had previously worked in the fur trade. Some of them turned to new trades, remained in the area and stayed permanently involved with their Indigenous families. In that specific context, the first generation of mixed-ancestry individuals had some social options available to them. While most remained associated with the local Anishinaabe communities, a few can be observed to have integrated into settler society. Overall, the number of these cases is limited.

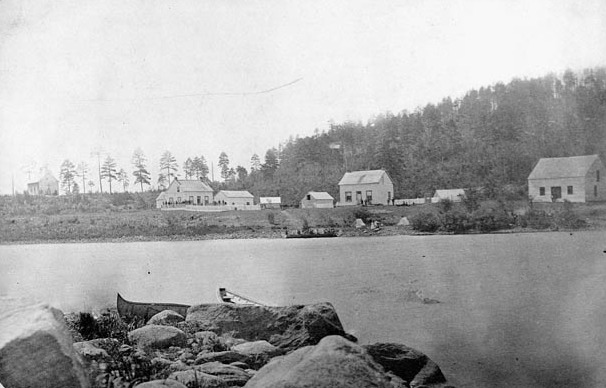

Source / Credit: George McLaughlin/Library and Archives Canada/PA-028725, http://central.bac-lac.gc.ca/.redirect?app=fonandcol&id=3228124&lang=eng&ecopy=a028725

To fully grasp the differences, one must consider the fur trade not only as a regional phenomenon but also as part of a continental network covering much of the North American hinterland. It was rooted in the northeast, with Montreal as the main seedbed from which this vast system took shape. Research on Métis ethnogenesis has often focused on the continental interior, where mixed-ancestry families clustered around key trading posts and gradually formed semi-sedentary communities, creating a new region separate from Montreal. By contrast, the Upper Ottawa region remained connected to the St. Lawrence Valley. Its posts were small, transient, and staffed by men who moved in and out quickly. Mixed-ancestry children born from these men were socialized as Anishnaabe alongside their mothers, leaving no critical mass to crystallize into a separate community. Unlike interior regions of the continent, where large fur trade commercial hubs such as Michilimackinac or Prairie du Chien emerged, the Upper Ottawa lacked both the demographic density and the structural conditions to foster ethnogenesis of separate, mixed-ancestry communities.

How did missionary activities influence the relationships between Euro-descendant men and Anishinaabe women?

When Roman Catholic missionaries arrived in the Upper Ottawa River area in 1836, they disapproved of country marriages when they involved Catholic men and strove to transform these temporary unions into permanent marriages, blessed by the Church. Not all country marriages underwent such a transformation. However, as Christianity became widespread by the mid-nineteenth century, permanent marriages became the norm for the men involved in the fur trade, and transient country marriages gradually disappeared.

Although unrelated to missionary activity, this change also coincided with the Hudson’s Bay Company reorganizing its workforce and employing fewer outsider single men. It also corresponded to greater endogamy in the second half of the nineteenth century, with members of settler society marrying among themselves and Anishinaabe people also marrying among themselves.

Source: “Michilimackinac, on Lake Huron : To his Excellency Sir George Prevost Bart. Governor General and Commander in Chief of all his Majesties Forces in British America. / This print is humbly Inscribed by his Excellency’s most obedient humble servant Richard Dillon Junr. ; Drawn by Richard Dillon Junr. ; Engraved by Thomas Hall.”. https://quod.lib.umich.edu/w/wcl1ic/x-6707/wcl006773. In the digital collection William L. Clements Library Image Bank. William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan Library Digital Collections.

Could you speak more about the sources you use?

A variety of primary sources were used and combined. We used documents produced by the North West Company, the Hudson’s Bay Company, and missionary records. Each one of those sources provides an incomplete perspective, but when used in combination, they offer greater insight into local social organization. We also make use of databases that record voyageur contracts and longitudinal genealogical studies. Finally, we place our research within a body of scholarly work and compare the area under study with the context of the fur trade in the continental heartland.

You concluded your article by stating that “…genealogical claims cannot be equated with the lived, cultural realities of historical Indigenous identities.” Could you describe more about the challenges Indigenous communities face today when responding to claims of Indigenous identity rooted in distant fur trade ancestry?

Several assertions of Métis identity, either political or presented before the courts, are based on genealogical claims. We have applied ourselves to examining social experiences instead. We found that the vast majority of children born to mixed unions can be shown to have adopted an Anishinaabe identity and be socially accepted as such by the Anishinaabe communities, while a few seem to have integrated into settler society. We found no evidence of a third, separate, mixed-ancestry community. We believe that the social context is an essential component to consider when attempting to determine if historical Métis communities existed in any given area.

Have you read anything good recently?

Leila: I have been reading about social categories in other colonial contexts. I have been particularly interested in Stephanie Guyon’s work on French Guiana.

Louis-Pascal: I read Michel Hogue’s Metis and the Medicine Line (2015), which I consider a major contribution to the historiography of Métis communities in North America. The book examines a population of mixed descent rooted in the fur trade on the Prairies during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, precisely when the Canada–U.S. border was gradually being established. At first, this line had little impact, but as Canadian and American state power expanded, it became a coercive reality that increasingly divided families and kinship networks. These groups —resilient to some extent through their pre-border patterns of mobility and contact— were forced to navigate rigid but differently shaped racial categories imposed by the two colonial states. Many found themselves caught in a limbo: recognized as “Métis” in Canada, or alternatively classified as “Indian” within one of the reserve systems on either side of the frontier, a colonial boundary so determinative of their existence that it came to be known as the “Medicine Line.” I find this study particularly fascinating because its comparative perspective shows how a political border can profoundly shape identity and the destinies of a mixed-descent population.

Jérôme Morneau: I am currently reading Paul-André Dubois and Maxime Morin’s “Guerre et population en Nouvelle-France”. The authors offer an exceptionally nuanced and detailed portrait of Indigenous demographics from 1680 to 1780. Their thorough legwork in the primary sources makes this book an indispensable reference tool for any historian seeking to document the demographic landscape of the period.