Derrick M. Nault is an assistant professor in the Department of Indigenous Studies at the University of Winnipeg and a citizen of the Red River Métis Nation. His current research examines Métis history, focusing on kinship networks, Indigenous allyship, and the role of storytelling and material culture in shaping historical memory and identity. You can read his article in the Journal of the Canadian Historical Association / Revue de la Société historique du Canada, vol. 35, no. 1 (2025) by clicking here.

Kinship seems to be a key theme in your article. Could you speak more about the role of kinship networks in the events surrounding the legend about François Guilmette?

When I began delving into François Guilmette’s background, I found very little information about him. I also noticed something odd on discussion threads about the famous “Louis Riel and His Councillors” photograph on Métis genealogy websites. Community members claimed to be descended from or related to most of the figures in the portrait. None, though, mentioned a connection to Guilmette. That silence and the fact that some posters said they were related to Charles Larocque (whom I later identified as the man standing behind Riel) made me question whether Guilmette was a real person. This was my first indication that kinship ties might be relevant for understanding events in the past like the Scott execution.

In a 2022 article I published in Prairie History,[1] I also found that kinship ties helped explain numerous aspects of the first act of resistance that took place during the troubles of 1869–70. This was the encounter with the Canadian survey team in which Louis Riel famously stepped on the intruders’ chain and said, “You go no further.” This act occurred on the hay privilege of my ancestor André Nault, who was Riel’s first cousin, and most of the men present were related to Riel or each other. As André Nault also participated in Thomas Scott’s execution, I was curious about the relationships among those involved in that event. As before, I found that most of the Métis were bound by blood or marriage ties.

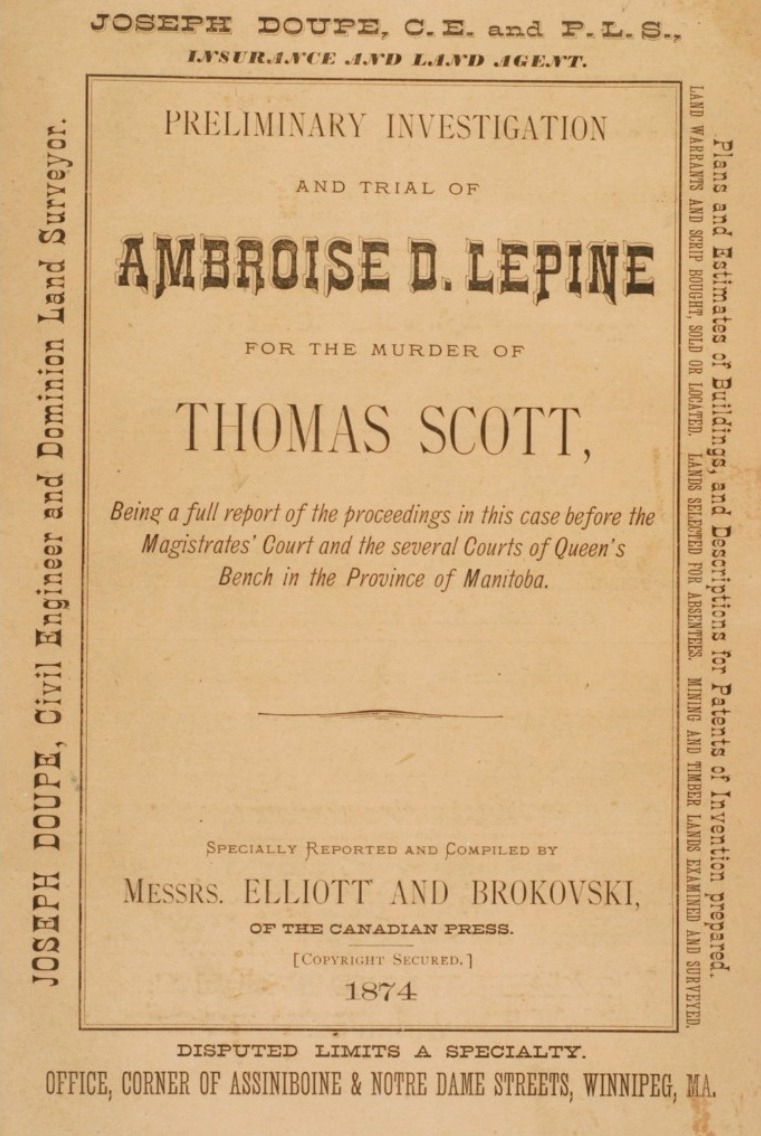

At the Ambroise Lépine Trial in 1874, at which Lépine stood accused of murdering Scott, most of the Métis cross-examined as witnesses once again were linked by kinship to one another or those involved in the execution. Where they weren’t, they were still staunch Riel loyalists. These witnesses mostly claimed not to remember key details about the death of Scott, except for the actions of “François Guilmette,” while non-Métis anglophone witnesses named several Métis participants, but not Guilmette. The different ways the two groups recalled the execution intrigued me and made me explore how kinship shaped each narrative. I began thinking that Guilmette was probably a fictitious person.

[1] Derrick M. Nault, “Louis Riel, Wahkohtowin, and the First Act of Resistance at Red River,” Prairie History 8 (2022): 5-16.

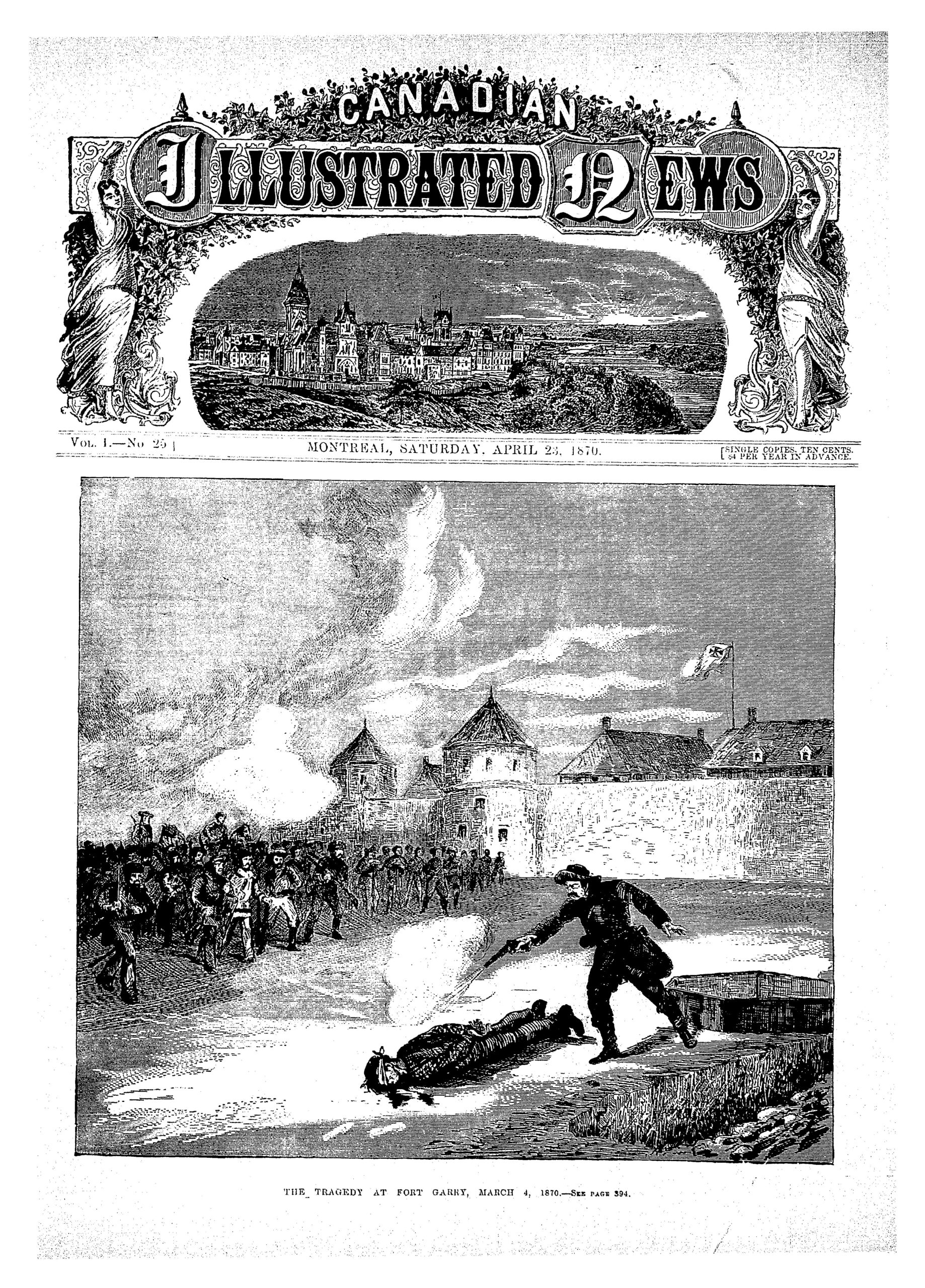

Figure 1. “The Execution of Thomas Scott,” Illustrated Canadian News, 23 April 1870. Available through Canadiana, a service of the Canadian Research Knowledge Network (CRKN), https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.8_06230_25/2.

Rumours and “miscommunication” play a big role in the stories about François Guilmette. Could you discuss more about how Métis and non-Métis perspectives influenced the narrative?

The first rumours about François Guilmette emerged amid the uncertainty at Red River that followed Scott’s execution, a time when it was hard to get reliable news. The Guilmette legend began as a vague reference in a news article in Le Métis, which mentioned that an individual named “Guimlette” had been killed by Riel opponents for participating in Scott’s execution. My theory is that the name was a garbled version of the family name of Elzéar Goulet. He was a captain in Riel’s provisional government who had served on the tribunal that voted for Scott’s execution. A US citizen, he operated a mail service from Pembina and was not based at Red River. Goulet was chased by Orangistes down Post Office Street (now Lombard Avenue in Winnipeg) and drowned after being struck by a rock as he attempted to swim across the Red River. On the same street where Goulet had fled was a shop owned by a “Peter Guilmette.” Since this was in the business district with a lot of people moving about, it was a perfect place for rumours to spread. Somehow, the name Guilmette became attached to the emerging legend. The full name “François Guilmette,” though, entered the public record during Ambroise Lépine’s 1874 trial.

During the proceedings, Métis witnesses re-used the name of a murder victim whose killer had been convicted in a highly-publicized trial in Quebec a few years earlier. The murder case was described in Canada’s first French language novel, L’Influence d’un livre (The Influence of a Book) (1837). The story would have been known to French-speakers at Red River but not their English-speaking counterparts. Since the imaginary Guilmette at Red River had allegedly been killed and was not from the Métis community, he could be blamed for Scott’s death, and enemies of Riel could feel vengeance had been served by his “murder.” Once François Guilmette was mentioned in the transcripts, however, it was accepted as fact by subsequent non-Métis historians, who embellished the tale further. The historian who contributed most to the legend was Father Adrien Morice, a French national who in his 1935 book A Critical History of the Red River Insurrection claimed the man in the Riel group photograph was Guilmette. As a result of Morice’s unfounded claim, Métis themselves eventually came to believe François Guilmette was not only the person who delivered the final shot that killed Thomas Scott but also a “councillor” in Riel’s provisional government. The true identity of the man in the photo, Charles Larocque, was gradually forgotten by many Métis. Family members were among the few who kept his memory alive.

Your article is revising Métis historiography and public memory! What led you to challenge the dominant narrative?

Input from the Métis community about an article I wrote in 2020[2] started the process. In that piece about the iconic “Riel and His Councillors” photograph, my idea was to clear up certain misconceptions about the image. For example, my article pointed out that the men in the portrait did not comprise Riel’s provisional government, as is often maintained. However, my article inaccurately labelled the man in the back row as François Guilmette and included the usual details about him participating in Thomas Scott’s execution. A Métis citizen from Edmonton, Patrick Stewart, reached out to me after reading the article. He suggested that the man in the image was a Larocque family member. Curious, I did some more research and concluded that he was right. From that initial conversation, I started questioning some longstanding assumptions about the Scott execution and the photograph.

What also led me to rethink the dominant narrative was the notion that Indigenous peoples only have “traditional” legends associated with rural settings in bygone eras. The idea that Indigenous peoples might create and share legends in urban centres in “modern times” has generally been overlooked by researchers. Of course, there are Indigenous authors, poets, and filmmakers who situate their stories in contemporary contexts and cities but few scholars have explored what might be called “Indigenous urban legends.” I was intrigued by where such a focus might lead me.

[2] Derrick M. Nault, “A Misleading Portrait: The Provisional Government of Assiniboia and the Creation of Manitoba,” Prairie History 3 (2020): 56-62.

Figure 2. Preliminary Investigation and Trial of Ambroise D. Lepine for the Murder of Thomas Scott (The Canadian Press, 1874), title page. Available through Canadiana, a service of the Canadian Research Knowledge Network (CRKN), https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.23952/6.[BB1]

Where is your research headed now?

I am currently working on two related projects. Both focus on my ancestors’ experiences during and after the two Resistances. The first project is about allyship and Indigenous peoples, which I explore using the example of my great-great-grandfather, André Nault. Despite having no Indigenous ancestry, Nault was born and raised at Red River and supported Métis causes throughout his life. He was a high-ranking officer in the military wing of Riel’s provisional government as well as an active member of the Union nationale métisse St. Joseph du Manitoba. I am interested in how Nault challenges conventional notions of allies as outsiders supporting Indigenous peoples for ideological reasons. I suggest that his relational ties to the Métis community and willingness to take genuine risks offers an alternate model for allyship that remains relevant for our own era.

My second project investigates a Métis beadwork collection at the St. Boniface Museum. The collection belonged to my great-grandmother Mathilde (Carrière) Nault. It was gifted to her by her mother Marie after her father Damase Carrière, a member of Riel’s “Exovedate,” was killed at the Battle of Batoche. Mathilde and her siblings were raised by an uncle in Manitoba, while Marie remarried another resistance fighter, Maxime Dubois, and remained in Saskatchewan. Rather than focusing on the features or artistic merits of the beadwork, I re-interpret the collection as a lieu de mémoire that conveys one Métis family’s struggles and adaptation following the Northwest Resistance. Mathilde married Alexandre Nault, a son of André Nault, and the beadwork at one time was displayed in their living room before being donated to the museum. The object thus ties two branches of my family and the two Resistances together. Recovering the family memories linked to the beadwork, therefore, is especially meaningful to me. In doing this work, I hope to preserve both family memory and this period in Métis history for future generations.

Have you read anything good recently?

Yes, I just finished reading Albert Braz’s The Riel Problem: Canada, the Métis, and a Resistant Hero (University of Alberta Press, 2024). Braz looks at how views of Riel in Canadian society have changed over the years to the point that he is now praised as a visionary who embodies Canadian values. This is in stark contrast to earlier understandings of him as a traitor and villain. The book mostly examines mainstream and official portrayals of Riel, but also includes a chapter on Métis perspectives, which Braz characterizes as somewhat ambivalent. Braz’s main argument is that critics and admirers alike have generally failed to understand who Riel really was because they have typically ignored his own writings. I think the book could have engaged more deeply with Métis voices, and Braz may overemphasize Riel’s psychological issues, but I still enjoyed reading it. It prompted me to think more about how Riel’s image has been misappropriated in ways that obscure the harm Canada inflicted on him and the Métis. My review of the book will be published in the Fall 2025 issue of Prairie History.